One year ago I was waist-deep in the New Fork River, due south of Pinedale, Wyoming. The mid-morning sun was warm against my neck and the air was bright and sweet on my lips. My short-sleeved button down tee dipped below my hips and caught in the flow of icy, clear water, tugging at my pockets and numbing my toes. The cold of the water brought me into a day that had begun without me. A kingfisher darted between its deadwood perches across the way; an osprey glided overhead. I could think of little more than the water against my legs.

The shallow riverbank was warm and I could see bugs hovering under drooping sedges.

“Morning duns,” my guide spoke from over my shoulder. “The fish won’t be biting on drakes.”

I handed my rod to the man, a seventy-something year old local angler with veined, sunspotted fingers that shook when they wrapped around the cork handle. He plucked my fly from the water and held it between his forefinger and thumb, holding it to the light before untying it from the leader. I watched as he opened his fly container and selected a tufted ball the color of his shock-white hair. He held it with his left hand while he searched for the end of the leader and poked the translucent fluorocarbon through a small hole at the butt of the fly. His hands never stopped shaking.

“This is a gray dun,” he held it up for me to see. “It mimics a mayfly, and the fish’ll bite on those. Cast near that rapid.”

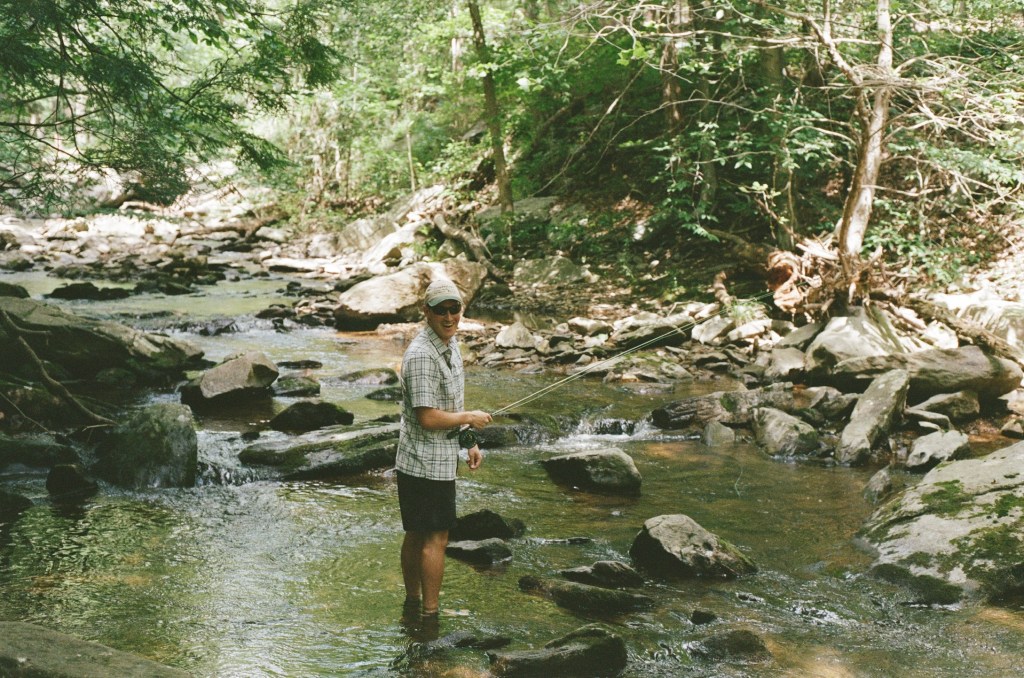

I took the fly rod in my right hand and held the line in my left, rocking the rod from ten to two, back and forth as he’d shown me. The fly lifted from the water and was airborne, blown dry in the wind. On my fourth false cast I sent the fly out toward the riverbank, letting go with my left hand. The fly floated in a gust and landed far from the rapid, in the center of the river. My guide gave me a look that said, try again. I did and on this cast managed to gain some distance, beginning to seek out seams between fast and slow currents.

From 8AM until around noon I stood in that river, taking instruction and learning to make my fly fall naturally atop the water’s surface. My guide showed me how to mend my line, lifting my rod and setting it down again upstream, downstream, reading the flow of the current. That morning I caught no fish. I took comfort in my guide, who shrugged that the fish weren’t biting and had no better luck himself. There was no shame in leaving emptyhanded, and I left thinking about the satisfying whisk of the fly line and the chill of the water against my shins.

Recently I’ve taken it upon myself to relearn the basics of fly fishing and become something of an angler. The transition from spin fishing to fly fishing can be difficult. Thankfully I have experience with neither, and I will be learning from a clean slate. In mid July I bought a beginner’s fly rod and reel from Orvis and a small collection of flies – a combination of nymphs (submerged flies that mimic aquatic insects in their larval phase) and dry flies (which sit upon the water’s surface). When I asked the man at the store which flies to buy, he looked at me with a cocked head and kindly pointed me toward the Parachute Adams and Ant patterns, explaining that they would yield the most success in mid-summer waters.

What follows is a catalog of my first fly fishing experiences:

July 15. Big Hunting Creek near Thurmont, Maryland. No catches. One bite that made my heart leap although I forgot to set the hook and it got away. Two flies lost – a Parachute Adams and an Ant.

July 19. Anacostia River in Wheaton, Maryland. Six catches, all micro-sized sunfish and bluegills. The water is too warm for trout. Fun enough to stand and practice my cast.

July 21. Anacostia River, again. No catches. No bites. One more fly lost to a tree branch. My legs are covered in mosquito bites.

August 27. Oaks Creek near Cooperstown, New York. No catches. No bites. Not a fish to be seen.

My early fly fishing experiences have taught me some things: get yourself wet, embrace the presence of bugs, do not rush the cast. More importantly, I have been learning what I still need to learn. So much of fly fishing, as it turns out, is studying the little intricacies of the river and its lifeforms. The key to fishing a river is a unique and quiet secret. Sometimes a hint will rise from a cold pool and, with only a nibble at your fly, it tells you that you’re in the right spot, that you are learning the river. And what truer goal is there than to know a place completely?

I have become accustomed to the sight of a naked hook – but despite my pathetic track record, I will keep at it. This morning, while standing in Oaks Creek, my attention was drawn from the glassy river current to a pair of Bald Eagles tracing the clouds above me. A Cedar Waxwing darted from a pine branch, joining the Goldfinches and Chickadees in the shrubs to catch the mayflies that blanketed the water’s surface. A family of turkeys squabbled away from the trail, spooked into an apocalyptic stampede. I saw that my interests in birdwatching and fishing intersected at the space between the hours of six and ten, that the fish are not the main event. The sunlight having come to warm the creek’s shallow pools, I packed my rod and left.