Monday, February 24: Rabat

The train groaned and rumbled on and the whole world came and went. A young medical student. An American businessman with a black laptop and too-short suit pants. An older woman in a pink dress with an oversized purple suitcase, which drifted to and fro with each lean of the railcar. No announcements were made and we tracked our progress through window-checks and anxious Google Maps refreshes. At sunset we could see the Atlantic and we arrived in Rabat just after dark. The Rabat train station was dirty and filled with shadows. Overworked lamps dotted the platform with pale splotches of white light where travelers lined the steps near the ticket booth. Tired and delirious, we stumbled onto the street. It was silent. Groups of people strolled along wide boulevards, lined with palm trees and massive government buildings. I could see the warm reflection of streetlights on the newly-washed pavement. Rabat stood in stark contrast to the bustling, pleading, dusty streets of Marrakech, and as we came closer to our riad in the medina we were near silent, simply registering the calmness of the city.

The riad was cheap and uncomfortable. We received our keys from a woman who used the telephone keyboard to explain to us the overnight fees. The television played a nondescript action movie. On the wall was a sign that read: “no shared rooms for unmarried or mixed-gender couples.” The walls were thin and the guests and employees were loud. We dropped our bags in our room, showered, and walked across the street to find dinner. One restaurant, Dar Naji, had a line that flowed past the front door, so we turned around and sat at a different spot near the tram stop. They served us large portions of tajine and rfissa, and we were full before our plates were half-empty. Next to us sat a middle-aged couple. The woman was French and her husband was half Belgian, half Moroccan. They spoke with us for a while about their vacation, a multi-week excursion in the south of the country. We told them about our trip and they recommended that we hire a tour guide to see the city, and that we rent a car to drive from Rabat to Fes. They were kind and we heeded none of their advice. We were very tired. With fatigue, we would begin adopting French mannerisms, saying tak tak tak and bah and du coup until we lost all focus and spiraled into fits of laughter. That night, we slept terribly. A couple fought on the phone. Three men arrived at 1AM, flooding the halls with noise. A woman suffered a ten-minute cough. The television stayed on until I finally ventured downstairs and muted it. There was nobody in the room to watch it, but thirty minutes later I heard it jolt back to life.

Tuesday, February 25: Rabat

I don’t remember my dreams but Ben said that I had been mumbling in my sleep. When my sleep is fitful and poor I say incoherent things, and I could hear Ben mumble too. We were groggy in the morning. I felt as though I had a mesh veil over my eyes and that my blood had welled near my cheekbones. We dragged ourselves to the café near the tram and I ordered coffee while Ben got cash.

We walked to the Quartier de l’Océan, a newer neighborhood just west of the medina, and bought pastries. My pastry-covered meat roll was warm and it was a relief to eat. With food in our stomachs, we strolled through a local marketplace and were spat out near the Four Seasons Rabat. The building looked like a palace, surrounded by high walls and overlooking the roaring coastline where gulls and plovers picked at invisible things in the sand. The cliffside hosted a public basketball court, an outdoor gym space and the National Museum of Photography. Visiting the museum had been on my to-do list but it was closed on Tuesdays, of all days. The building itself was a sight to see, with its sweeping concrete curves, walkable ramps and clifftop steps, families of stray cats sleeping in shaded corners. The wild waves kicked up a fine mist that filtered the midmorning light into a gauzy hue.

Our walk took us past the lighthouse, where a family was taking photos on the front steps. We stopped near the water and quickly had to retreat to keep from being soaked by a wild wave. On the other side of the coastal highway, a massive graveyard covered the hillside like a bedsheet. It looked full and I wondered how long it had been there. What had been there before the first grave had been dug? It sure was a nice view from that hill. We paced the public beach where people swam, children kicked around a ball, and a man lounged, brewing tea. Soon we were passing through the tight, white-walled streets of the Jewish quarter. The walled neighborhood was up high, overlooking the beach and the medina, and hunger pulled at my gut as we were dumped back onto the cobbled market roads.

Tracing our way through the medina, we passed stalls selling neatly-organized junk. On a tattered carpet, knock-off luxury hats, displayed proudly. Where one hat had been removed from the display, a stray cat lay curled into itself. Though the streets were dusty and busy, the medina was surprisingly comfortable to walk through. Where in Marrakech vendors stepped on your toes, in Rabat the sidewalks were wide and open. Eventually we passed the original entrance to the medina, near our riad, and we took a left turn into the administrative district. An expresso in the shade gave us energy to search for lunch, but we were hungry. Ben found a restaurant, but it was closed. I found a restaurant, but it sat on a deserted street and emitted an energy that was underwhelming and yet undeniably menacing. We were hangry and had had enough of Google Maps’s suggestions. We took a turn towards an open square, where we found a lowered food court shaded by iron trees. Lunch was very good if, as usually was our experience with Moroccan food, very filling. The restaurant had a vast selection of drinks (e.g. lemonade (lemon juice with water), mojito (lemonade), and something called a panaché (a mix of lite beer and lemonade)) and a bathroom with a very wet floor. We ate slowly and left.

Our next stop was Chellah, an ancient hilltop city. Chellah was originally the site of a Phoenecian trading emporium during the first millenium BC, and was reconstructed by the Romans around 40 CE. Later, in the 13th century, the Marinid dynasty transformed it into a necropolis. The ruins at Chellah hint at millennia of human settlement, with carved pillars and the crumbled foundations of a Marinid madrasa standing resolutely at the foot of a lush garden. The footprint of a Roman forum lies a few meters from the remains of a 700 year-old hammam. The madrasa, which lies within a larger funerary complex called a khalwa, once hosted hundreds of students. Nowadays its crumbled walls are home to nesting storks. As we walked through the large stone gateway and onto the mosaic floor of the complex, we were overwhelmed by an unsettling rattling. The white storks glared at us from their perches, rapidly clacking their beaks and shifting to one side or the other. We left the complex, passing a lone peacock and an eel-less eel pond on our way to the public restroom, where a woman stood at the doorway collecting a small fee. I felt giddy.

That night we ate at a tapas restaurant where we ordered patatas bravas, chorizo and a shrimp dish that would throw us into a deadly downward spiral.

Wednesday, February 26: Rabat to Fes, via Meknes, Azrou and Ifrane

The second night at Riad El Mesk was not much better than our first. Guests arrived throughout the night and the television was left on, again. I borrowed ear plugs from Ben and eventually fell asleep.

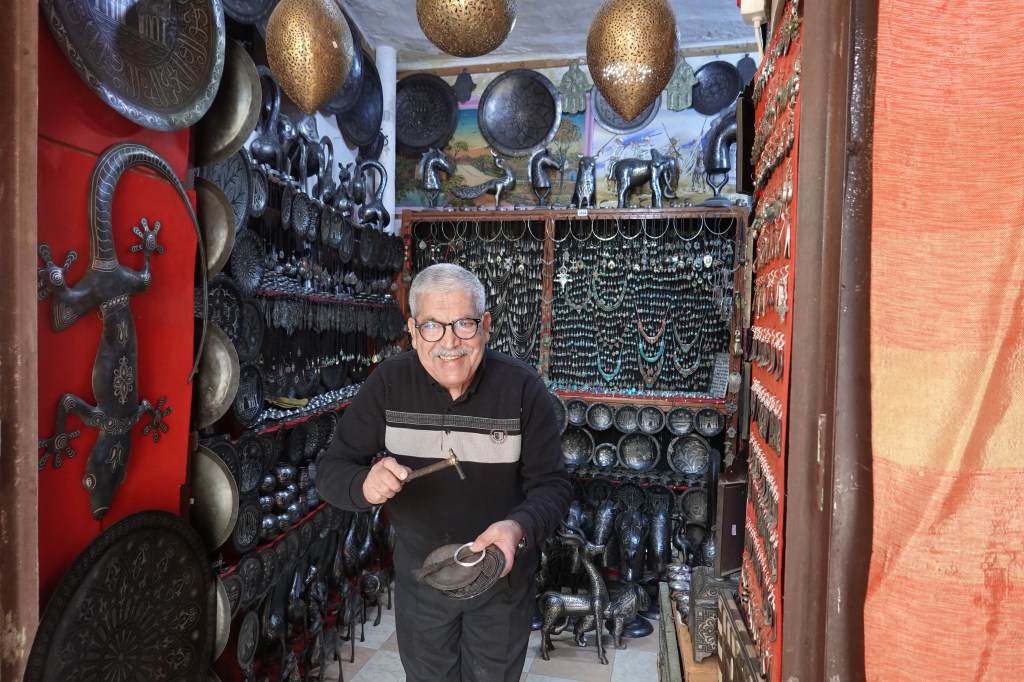

In the morning we were relieved to be on the road again. We met our driver, Hassan, at 8AM near the medina and drove to Meknes, Morocco’s sixth largest city and its fourth imperial city. Meknes is known for its ancient ruins, its medina and massive gateways like the impressively ornate Bab Mansur al-Alj’. The ruins were closed for restoration, but we took the time to wander through the medina. In a tucked-away nook we found stalls of artisans polishing marble engravings, refining and staining wooden chairs. In one stall we met a man who sold authentic damascene steel goods. The walls of his workshop were lined with black metal boxes, pendants, rugged animal sculptures, all intricately overlain with designs of shining silver. He taught us about the process of making damascene, an endeavor that takes multiple people and many hours to complete. First, the metal is shaped and even welded into form. Then, grooves are scratched into the surface so that when the silver string is hammered onto the steel, during the next step, it sticks. At this point the whole item is scorched, left to cool, and polished with stone, before being burned again. Finally it is polished with lemon juice and wiped with olive oil. The result is a nearly indestructible piece of art.

Ben and I each picked up a few items. I chose a dish and a soot-black dolphin. Then our attention was drawn to the room in the back of the store, which was filled with beautiful Amazigh rugs. The man enthusiastically showed us his collection, explaining to us the difference between four styles of rug. In Marrakech we had been given a similar demonstration by a high-profile rug merchant. The nonchalant character had gone to great lengths to let us feel the highest quality of rug alongside the worst, and in the end he high-balled us. We didn’t bite. This time, the prices were reasonable and we could tell that the quality of the rugs was good – the weave was tight, the colors were natural and the pattern unique. Ben bought two rugs for himself and one more as a gift.

Hassan drove us from Meknes to Azrou, a mountain town known for its handcrafted goods. We visited a nearly empty cultural center and spent a few minutes standing in front of rocks, traditional dress and a human skeleton. I wondered about that body in the glass box, filling space in a dark room between the bones of an ancient tiger and a long-extinct European elephant. Behind the cultural center was a building with artisanal workshops, where a kind woman sold us hand-made spoons, bowls and figurines, each made from wood from the local cedar forests.

At Ifrane National Park, we shared mint tea among 300-year-old cedar trees and troops of endangered Barbary macaques. The animals leaped between the branches above us and ventured into the picnic area to swipe food from tourists. I wasn’t expecting the monkeys, a quarter of the species’ global population, to be so accustomed to visitors but they kept close to the tea counter and waited for snacks to tumble onto the sap-covered earth. I was excited to see the macaques but it made me sad to know that an animal whose existence has been jeopardized by deforestation and human development has become dependent on food scraps left by tourists – some of whom have illegally caught the monkeys, further reducing their numbers. I took photos and we left, en route to Fes.

Before reaching Fes we stopped in the town of Ifrane. The community is settled near a ski resort and felt lifeless in late February. Rows of massive houses, some clearly empty, lined the streets. The town center itself felt like a movie-set version of a ski town, with its faux-Aspen A-frame buildings and unsettlingly vacant sidewalks. I imagined that the buildings were facades. I was extremely tired and, I suspect, feeling the effects of the prior night’s shrimp dish. The world had begun to take on an unusual aspect. Floating through the countryside, we reconnected with the main road and as we entered a sizzling new landscape we glimpsed an aerial view of the largest pedestrian area in the world: the medina of Fes. That night we took our first tentative steps into that mess of passageways and dead-ends, with a late dinner on a rooftop terrace. We walked to our riad, or tried to. We hit one dead-end, and then another. The path we meant to take was closed and we turned around twice before arriving and settling in for a restful night.

Thursday, February 27: Fes

It was not a restful night. I slept poorly, waking up several times throughout. The next morning I woke up with a headache and a general detachment from reality, and it wasn’t until we had walked for thirty minutes throughout the medina that I finally felt like myself. The sun was strong and flooded through the criss-crossed panel roof of the medina. By now we had ditched Google Maps and were navigating via an oversimplified paper map from the riad check-in desk. The warmth of the day filled me with renewed energy and we walked a loop through the medina. After half an hour we popped out into a large square called Bou Jeloud, paced through the public park and meandered into the Jewish quarter.

We paused at the entrance and sipped a coffee. We didn’t drink water. The streets were busy with salespeople, their goods laid on carpets on the road. Young men sped by on motorcycles. We were hot and I wished that we’d bought sunscreen. It was sold at hundreds of stalls throughout the city and we never bought any. In the Jewish quarter we passed a sprawl of shops, each selling fake luxury goods and soccer jerseys. They sold electric razors and flip-flops, sneakers and djellabas, graphic tees and cigarettes. Everything was factory-made. Everything was the poorest of quality. Even the shop mannequins had crooked faces and missing parts.

I was both disgusted and in awe of the quantity of useless junk that lined the path. There must have been a time when people came to Fes for hand-crafted leatherwork and fabrics, for high-quality woven goods, for pickled foods and worldly spices. There must’ve been a time when the streets were not littered with fast-fashion items. I kicked myself for thinking about this and for adopting the tricky habit of romanticizing a less globalized past and rejecting the present reality. The Fes of my imagination may have never existed at all and the modern market, with its centralized taxi services and quality control, may be much safer than it was fifty or one hundred years ago. Still, I was repulsed. I watched as one person after another walked straight past these stalls. Nobody believed in their quality and nobody purchased their items. It struck me that the majority of those shirts, shoes and hats would end up in a trash heap without ever having been worn. The potential waste was staggering. The clothing, so cheaply acquired, was under no expectation to be sold at all.

It is estimated that more than 80 billion garments are produced every year (as of 2015), a number that rises annually (higher estimates reach 150 million items). Fast-fashion is the second largest consumer of water behind agriculture, and is responsible for 20% of global wastewater. The production of a single cotton shirt uses 700 gallons of water, and the chemicals involved can and has severely damaged local ecosystems. What is the reward, but millions of unsold and unworn tee-shirts littering cities like Fes and choking the ecosystems that sustain them.

We retraced our steps until we found ourselves back at Bou Jeloud. This time we took a left turn and followed the main road up the hill to the university-hospital complex. We spoke with a friendly guard who smiled and told us about his American sister. He was happy to meet Americans and sounded relieved to engage in conversation after a long shift. We were beginning to fade and we continued our walk along the cliff towards a hotel café that overlooked the vast medina. We could see the historic madrasa and our riad, and just behind it a jumbled building that was shrouded in thick steam.

That morning we had dragged our feet as we left the riad and had visited the tannery. The complex, one of three still in operation, was unmissable, just behind the riad. We walked straight until we came to a crossroads and were slapped across the face by a putrid stench. The smell was overwhelming, unlike anything I had experienced, and as we approached the tannery a man led us to a rooftop and gave us bundles of mint to place underneath our noses. From the rooftop we watched workers wade through pools of milky white water. Some puddles were a deep brown while the rest were nearly black. They all smelled of death. I took deep inhales through my nose and then held my breath. The workers did not carry mint and I worried for them. I worried more when I heard about the tanning process itself.

First, hides are broken down through a long soak in – you guessed it: cow urine. The urine is mixed with salt, quicklime and water to remove excess hair and fat. Then the hides are taken from their cow-piss baths to a new set of baths filled with water and – yup: pigeon shit. The workers knead the hides with their bare legs to soften them enough for the dyeing process. The hides are placed in pools called “death pits” and are dyed with natural dyes like saffron, poppy flower, and cedar wood. Finally, the hides are dried. At the tanneries of Fes, this medieval operation has remained nearly the same since the 13th century.

We could see those steaming vats of pigeon shit from the hotel café, and as we ordered cold beers and sandwiches I could still smell it on my clothes. The beer was heavenly. The sandwiches were sublime. The path home took us down a dirt-covered ridge where a flock of sheep trodded past discarded chip bags and soda cans. A horse stood very still until it exhaled sharply and flicked its tail. We had sunstroke.

That night we bought knock-off luxury sunglasses, picked up ceramic goods and had dinner at the same restaurant that we’d eaten at the first night. The waiter did not recognize us. Back at the hotel I drank two large bottles of water and I was still dehydrated. I got the shivers and at some point I fell asleep.

Friday, February 28: Fes to Casablanca

I woke up at 5AM, thirsty. I stumbled downstairs to the lobby where I expected there to be a concierge, but there was nobody around. We had no water left, the tap-water was unsafe to drink, and I was parched. I had no choice but to go back upstairs and try to sleep. In the bathroom I swished my mouth with water and spat it back out.

I woke up again at 7AM. If I didn’t have a drink of water I would shrivel up into a husk. This time, however, the concierge was at his desk and he must have seen the look of desperation on my face because he gave me the water bottle for free. I drank the whole thing and fell asleep for another hour.

At 9AM Ben went downstairs for breakfast. At 9:30AM he came back upstairs. At 9:45AM I went downstairs for breakfast. At 10:15AM I came back upstairs. I was wrecked but Ben was not feeling at all well, and we took a quick walk through the medina to wake ourselves up. It was only hours from the beginning of Ramadan and most of the stalls were shuttered. The streets were calm and we found a man selling knock-off watches. Half-awake, I browsed his collection as he spoke at me about quality and water-proofing and the merits of manual watches versus automatic. I was looking for a watch for costume parties and bought a cadmium-faced Rolex for 25 dollars – a perfect pairing with my new Gucci sunglasses. At 10:45AM we were led to a taxi who took us to the train station and over-charged us. We were too tired to hassle.

The train rolled on for three hours, past Meknes and Rabat, before grinding to a halt in Casablanca. The business capital’s prominent white-walled buildings greeted us, poised like dominos. That morning I had felt nearly immobile, as if some small mischief-maker was tugging at my insides. When we got to Casablanca I felt closer to normal. We dropped our bags at our hotel, took half an hour to catch our breath, and marched into the center of the city. The neighborhood quickly became residential. Families crowded the streets, forming queues at market stalls. Ramadan would begin at sunset and the atmosphere in town was frantic. Kids ran through the street. Two women fought outside a supermarket. Seagulls wailed, a massive flock in the sky. Beyond them a storm clashed and darkened as we approached the Hassan II Mosque. The wind picked up and the seaside mosque, the third-largest in the world, towered above the city, its minaret surging into the churning sky. The first drops of rain fell softly and soon we were caught in a deluge. We ran to a waterfront café where our waterfront view was obstructed by a waterfront highway. It was good to be still. We drank tea and ate green foods as the storm raged and abated, leaving the asphalt coated in a salty dew.

That night: a confused older woman mistakenly enters my room, I say goodbye to Ben, and I fall asleep at 9PM.

Saturday, March 1: Casablanca to Bordeaux

My flight home was meant to leave at 8AM. Two days after arriving, the time was shifted back one hour, meaning that, incredibly, my flight now departed at 7AM. I like to give myself two hours of working time when traveling through a new airport, a luxury that meant ordering a taxi for 4:15AM.

What had begun as a smooth trip had, in the final days, hit some bumps. A hellish hotel, possible food poisoning, heatstroke, a thunderstorm. My early flight was the final hurdle, and despite the challenges I was proud of our planning and execution. Ben would be taking the next afternoon’s train to Marrakech and flying out from where it all began.

I do not remember snoozing my 4AM alarm. At 4:10 I rolled out of bed, grabbed my bags, put on a baseball cap and ran downstairs to where the taxi driver was waiting for me. He was silent and I was silent. Loading my bags into the backseat, we rushed away from the hotel and sped through two stop signs. The markings on the road were little more than suggestions. We passed large shipping trucks and construction workers. I had never told him where I was going.

“Hey,” I said uneasily.

“The airport,” he replied, “yes.”

I sighed.

He ran four red lights before we arrived at the airport. Two hours later, I was on the plane and on the runway. One hour after that, I was still on the runway, listening to the mumbles and sighs of eighty-odd unsatisfied Frenchmen. I closed my eyes and I was home.